![]()

by Alexandra Isfahani-Hammond

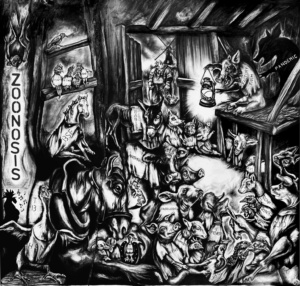

Zoonosis by Sue Coe.

2022 marks the third successive year of a global pandemic borne of a virus transmitted to humans in the Huanan Seafood Market, where up to 75 different animal species were routinely slaughtered on site while others observed from their cages. Though unprecedented in scope, COVID-19 is merely the newest in a string of zoonotic illnesses borne of extreme suffering, including in the industrialized “wet markets” of the West known as slaughterhouses. The practices of confining, breeding, slaughtering and consuming animals have given rise to the deadliest epidemics in recent history, including Ebola, SARS, MERS, Bird Flu, Swine Flu and the seasonal flu. Scientists predict that an even more severe zoonotic disease is on the horizon. In the early months of the global shutdown, there was speculation that attendance to humans’ treatment of other species and the natural environment might finally take center stage as an imperative socio-political concern. In her essay, “The Pandemic is a Portal” (4/3/20), Arundhati Roy conjectured that COVID-19 could ignite a reckoning. Was it possible that our extractive orientation to the earth and living beings could pivot to an economy of care? With COVID-19 cases back on the rise, is there still a chance we could change course?

As it happens, Wuhan’s caged pangolins are conceptually related to a Big Apple pachyderm, since the legal battle centered on Happy, a 52-year-old elephant in the Bronx Zoo, points in the direction of such structural transformation. Though her case has received significant media attention, it has not yet been placed it in the context of the incarceration of “food” animals that led to COVID-19 and Roy’s persuasive admonition that “Historically, pandemics have forced humans to break with the past.”

The Nonhuman Rights Project has been advocating on behalf of Happy since 2019. On February 18, 2020, they argued before the Bronx Supreme Court that she is a person, not a thing, invoking the writ of habeas corpus to achieve her release to a sanctuary. Happy’s bio belies her name: following capture in Thailand along with six other calves, an event that almost certainly entailed killing her mother and other herd adults who would have fought to protect her, she has spent nearly her entire life either in a one-acre enclosure with an indoor holding area, or a barren, cemented, walled outdoor elephant yard, miniscule fragments of the natural home range for Asian elephants that can reach up to 600 square kilometers. Whereas elephants normally live in complex societies, forming strong, lifelong social bonds, Happy has lived in isolation since 2006. She spends much of her time standing in place, swinging her trunk and raising and lowering her feet, standard examples of “zoochosis,” defined by ethologist Marc Bekoff as the “repetitive, functionless behavior caused by the frustration of living in a highly unnatural and impoverished environment,” itself akin to “psychological torture.” While Bronx Supreme Court Justice Alice Truitt did not accede to the NhRP’s plea, she declared that she was sympathetic with their mission on Happy’s behalf and referenced New York Court of Appeals Judge Eugene Fahey’s 2018 statements that “the issue whether a nonhuman animal has a fundamental right to liberty protected by the writ of habeas corpus is profound and far-reaching” and that “Ultimately, we will not be able to ignore it.” Happy’s attorneys will appeal Tuitt’s decision on May 18, 2022, marking the first time that the highest court of any U.S. jurisdiction will hear a habeas corpus case brought on behalf of someone other than a human being.

Habeas corpus has already been employed successfully to protect members of other species in Brazil and Argentina. The first time in history that a court agreed to consider the writ of habeas corpus on behalf of a nonhuman animal was in 2005 in Salvador da Bahia, Brazil, when attorneys representing the Animal Abolitionist Institute sought release of a chimpanzee named Suíça from solitary confinement in the Getúlio Vargas Zoo. They argued that chimpanzees are highly social creatures who exhibit stress symptoms including self-mutilation, dysfunctional sexual behavior and evidence of autism if deprived of socialization, in addition to the hardship of unrelenting exposure to onlookers. Judge Edmundo Lúcio da Cruz determined that Suíça’s case merited serious consideration — and, hence, that a nonhuman animal might indeed be recognized as a subject of the law — but Suiça was found dead in her cage before the case was concluded.

Another habeas corpus case in Salvador da Bahia achieved direct benefit for the incarcerated. In 2010, attorneys from the Brazilian Association of Green Living Earth and Mother Cell Association represented two elephants, Guida and Maia, arguing that they were being unethically and illegally detained by the Portugal Circus. Judge Ana Conceição Ferreira determined that Guida and Maia were rights-bearing subjects and ordered their transference to a sanctuary. Ferreira affirmed their dignity and spirituality and the artificiality of the anthropocentric view that animals are inferior to humans. The court stressed the need to imagine humans in reciprocal and respectful relations of solidarity with nonhumans, lamenting “the destructive nature of human beings” and declaring that “As subjects of rights, any action that demeans or tarnishes the dignity of their lives is inherently illegal and must be repudiated and banned.” Ferreira cited philosopher Tom Regan that “any and all animal exploitation is immoral and violates a natural law: respect.”

Other successful cases include the 2015 habeas corpus trial on behalf of Sandra, an orangutang in the Buenos Aires Zoo. Hearing testimony from the Association of Employees and Attorneys for Animal Rights and attorney Andrés Gil Domínguez regarding Sandra’s innate entitlement to freedom of locomotion and protection from physical and psychological harm, Judge Elena Libertori determined that she be relocated to a primate sanctuary in Florida. Libertori explicitly recognized that Sandra was a “nonhuman person and subject with rights.”

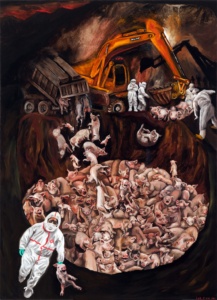

Death Pit. Image: Sue Coe.

While it did not involve habeas corpus, the 2000 Indian case of Balakrishnan et al v Union of India also demonstrates judicial commitment to abolishing the instrumentalization of animals. The court upheld a government notification prohibiting the use of bears, monkeys, tigers, panthers and lions as performing animals, stating “(m)any believe that the lives of human(s) and animals are equally valuable and that their interests should count equally” and that legal rights should be extended beyond human animals, “thereby dismantling the thick legal wall with humans all on one side and all non-human animals on the other side.”

Legal scholar Gary Francione argues that nonhuman animals need to be classified as persons, not property, to safeguard their rights. This is because no matter how much attention is given to their welfare, as long as their status is that of property, their interests, consent and autonomy will not be meaningfully taken into account. It is important to note that legal personhood is not equivalent to human status. It is also crucial to recognize that right wingers invoke fetal personhood and that corporations are legal persons in the U.S. But by contrast with the weaponization of personhood status in the service of patriarchal and neoliberal agendas, personhood has been widely utilized as a tool for dismantling carceral logics and for redressing the commodification of the environment. Mountains, forests, rivers and ecosystems have been legally classified as persons. The rights of nature “to exist, persist, maintain and regenerate its vital cycles” were proclaimed under Ecuador’s 2008 constitution. In 2010, Bolivia passed the “Law of the Rights of Mother Earth,” designating Mother Earth as “a collective subject of public interest” with aspects of legal personhood and inherent rights specified in the law. Switzerland’s constitution contains an “animals are not things” declaration and recognizes the “dignity of living beings” in what is known as it’s “dignity of the creature” provision, while Brazil’s 1988 constitution prohibits subjecting animals to cruelty, India’s describes “compassion for living creatures” as a “fundamental duty” and German civil code includes the statement that “animals are not things.” Legal scholar Maneesha Deckha observes that, for the most part, the potential of such language has been thwarted by speciesist bias; causing harm to animals remains legally justified in the service of human interests, such that other creatures are “amenable to a cost-benefit calculation.” Deckha nonetheless affirms that inclusion in a constitution is “a significant symbolic step towards repositioning animals from exploited property to respected beings” (“Constitutional Protections for Animals: a Comparative Animal-Centered and Postcolonial Reading,” 2020).

Rejecting human exceptionalism constitutes a moral and spiritual about face, but it’s not remotely a new idea. In the early twentieth century, Charles Darwin taught us that species are on a continuum; humans are merely one kind of animal, a member of the strata of great apes: orangutans, bonobos, gorillas, chimpanzees and humans, all part of the family Hominidae. The similarities don’t stop there; for instance, pigs and humans share approximately 98% of the same DNA. While Darwin’s scientific observations are, in theory, widely accepted, our perseverant attitudes remain tethered to pre-twentieth-century thought. They are informed by a concept known as “the great chain of being,” a hierarchical model of all matter and life, with humans at the top, thought in medieval Christianity to have been decreed by God. The second idea upon which our relationships to other species is based is the philosophy of the early 17th-century scientist René Descartes. In Descartes view, animals are objects without feelings, much less intelligence or the right to live without being held captive or subjected to gratuitous violence. His most famous experiment involved nailing a dog to a board. As he began cutting into her chest, she screamed and struggled to free herself. Descartes said that her reactions were akin to the sputtering of a mal-functioning machine; in other words, he interpreted her agony not as agony but as no different from an engine running out of steam.

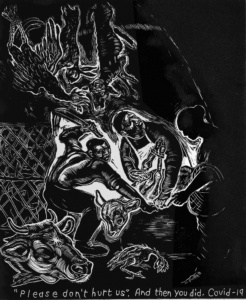

“Please don’t hurt us.” Image: Sue Coe.

Most people would say Descartes’ vivisection of the dog is barbaric and outdated. However, our current treatment of animals, whose consent and autonomy we consistently override, resembles Descartes’17th-century mindset rather than Darwin’s. Approximately 150 billion nonhuman animals are subjected annually to the most brutal suffering in animal agriculture, while approximately 115 million nonhuman animals are used in scientific experiments annually worldwide. Most people do not know what occurs in these places. How many readers are aware that beagles are hooked up to hoses inhaling cigarette smoke until they expire, simply to determine what we already know, that tar and nicotine are indeed toxic? Or that it is standard industry practice to cut off piglets’ ears and tails and to castrate bulls, all without anesthesia? That infant monkeys are subjected to maternal deprivation experiments where they are kept in isolation without touch or contact of any kind, simply in order to determine whether they will decline and die from such deprivation? That male chicks, useless to the egg industry, are killed by feeding them into grinders while fully conscious? Or that dairy production is dependent upon forced reproduction and the repetitive, constant disruption of the mother-child bond, with mother cows wailing for calves taken from them soon after birth and auctioned, often with a few inches of umbilical cord still intact and dripping with uterine fluid, as veal? These examples are not aberrations but, rather, the norm. In short, we continue to operate according to the Cartesian idea of animals as unfeeling beings, mere commodities, regardless of what Darwin told us about our similarities. It is imperative to stress that membership within the human species is itself no guarantee of the protections from gratuitous harm and incarceration afforded by “Human” status, since whole categories of humans have, throughout history, been characterized as “animals” and, therein, subjected to legally and morally condoned confinement, commodification and death, all to uphold and preserve an ever-shifting, culturally and historically contingent “inner circle” of moral protection.

Our adherence to the Medieval notion of the great chain of being has proven catastrophic. The current geological age, known as the anthropocene, is defined by human devastation of the earth — including burning fossil fuels, the destruction of rain forests and the pivotal impact of industrialized animal agriculture on global warming — making it increasingly uninhabitable, while the adage that “we are all connected” is borne out by COVID-19: nonhuman animals whom we subject to the bleakest of lives disseminate contagions borne of the endless suffering we inflict upon them, literally taking our breath away. Critics fret that nonhuman animal personhood is a “slippery slope”; if we acknowledge that Happy is a subject of moral concern, where would we draw the line? But what if we stopped grasping for the brakes and allowed ourselves to arrive at the passageway envisioned by Roy, abandoning our extractive approach to other-than-humans as mere commodities to entertain, feed and labor for us and to experiment upon, embracing what is in fact not such a novel way of thinking? Like the Asteroid in Adam Mc Kay’s “Don’t Look Up” (2021), zoonotic disease poses an existential threat that drives home the urgency of reorienting our relationships to other species. Darwin was ahead of his time. Can we catch up to him? Our survival depends upon it.

Click here to watch the New York court of appeal’s livestream of arguments on behalf of Happy on May 18, 2022: https://www.nonhumanrights.org/blog/Highlight_Page/the-fight-to-freehappy/.

Alexandra Isfahani-Hammond is Associate Professor Emerita of Comparative Literature and Luso-Brazilian Studies at the University of California, San Diego. Her publications on Critical Animal Studies and the legacies of African enslavement include “Haunting Pigs, Swimming Jaguars: Mourning, Animals and Ayahuasca”(2019), “Akbar Stole My Heart: Coming Out as an Animalist” (2013), and White Negritude: Race, Writing and Brazilian Cultural Identity (2008). Her current book project, “Home Sick,” blends theory with creative nonfiction to meditate on grief, end of life, the medical-industrial complex, Islamophobia and the commodification of (human and nonhuman) animals.